The dream of many writers is to be traditionally published. There is a certain amount of clout that comes with having a manuscript printed by a company that is in the business of publishing books. There is a validation when an author’s book is distributed to brick and mortar bookstores like Barnes and Noble. I understand the appeal, but the more I learn about modern traditional publishing, the more I find it antiquated and bizarre.

Is traditional publishing behind the times?

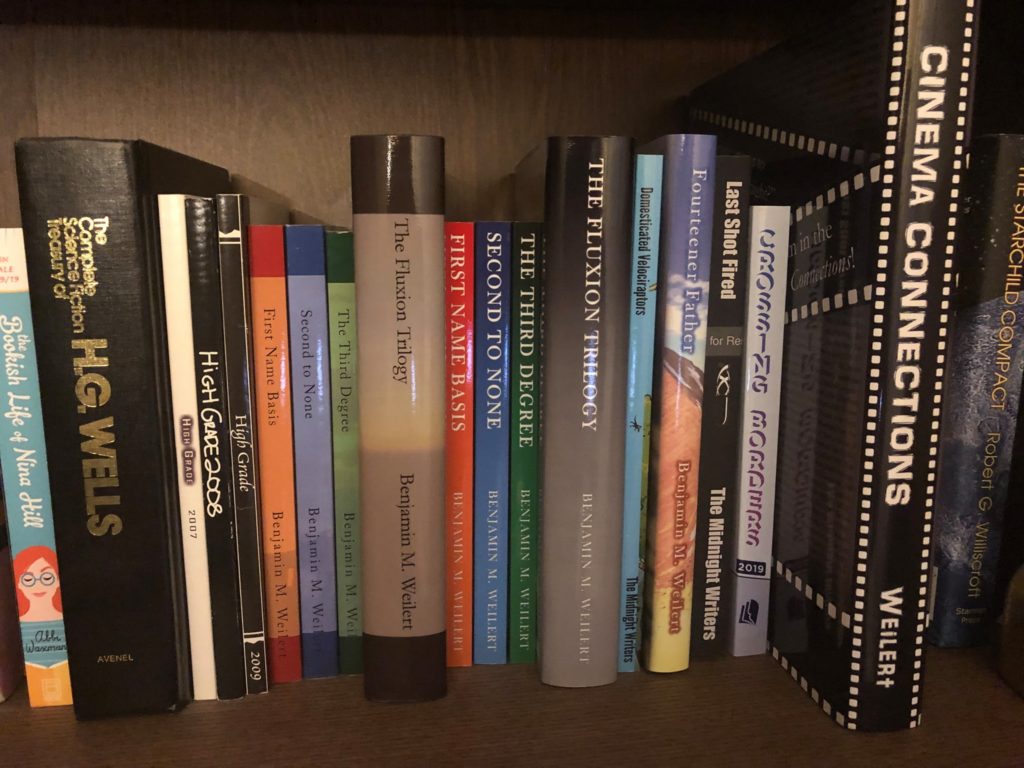

For personal reasons, I have decided to exclusively pursue self-publishing as my venue for distributing my stories. While this is in part due to my realization that I can’t make a living off my writing—and thus why I pursue it as a hobby—I’ve dipped my toe in enough of the process and discussed it with other lesser-known authors who have successfully done it to realize that it’s somewhat stuck in the past. Here are three things about traditional publishing that I find bizarre:

1. Agents

As an author, the concept of an agent seems like an extra step to getting published. In simple terms, I would basically hire someone to go to publishers and present my manuscript for consideration. This seems like I’m hiring an intermediary for a process that should only be between two entities. Sure, I understand that the agents have the “connections” to get a book into traditional publishers’ hands, but isn’t that what the internet is for? Can we not connect with millions of people (and companies) through our computers? Why, then, do we need a person to connect us with a publisher when the publisher clearly has a website with a “contact us” section?

I find agents to be an extra layer of gatekeeping on top of the gatekeeping of traditional publishing. Not only do you have to have a story that interests the publisher, but it also has to interest the agent who pitches it to the publisher as well. Perhaps my perception is wrong, but from most of the agent descriptions I read on querytracker.net, the agent I get is only interested in the manuscript I’m querying and not the multitude of other ideas I might have. Do I then have to get a different agent if I want to write in vastly different genres? Say I get an agent who does sci-fi, but then my next book is literary romance, which they won’t touch with a 6-foot pole. If they are my agent, should they try and get a publisher interested in it even if they themselves are not? Maybe an agent makes sense if an author is only going to write in one genre, but that seems constraining to me.

2. Distribution and Marketing

There was a time when the only way people could buy your book was if they went to an actual bookstore and bought it there. As far as I know, the only bookstore that’s left is Barnes and Noble. Even though they have managed to provide independent authors with methods of getting these books on their shelves in recent years, what extra benefit does the traditional publisher provide? If they’re distributing to smaller local bookstores, I can see some benefit, even though those stores are disappearing at an alarming rate. Anymore, people buy straight from Amazon, which is one of the premier resources for self-publishing (I refer, of course, to Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP)).

Authors seem to think that a publisher will put a lot of money into marketing their book. The trouble with that is—from the anecdotes I’ve heard—they don’t. They expect authors to come to the table already flush with followers and readers who will automatically buy the book they will be publishing. I ask, then, if these followers would buy the book anyway, why does it need to be from a traditional publisher? Sure, the publisher does marketing, but only for the “brand” authors already well known. They aren’t going to take a risk on some unknown or first-time author.

3. Rejection

Traditional publishing normalizes rejection. This feels backward to me. Sure, I know there are many stories out there, and not every one of them is marketable. That being said, even when authors spend so much time researching agents (and publishing houses that accept open submissions), their acceptance rates seem abysmal. Perhaps the reason why rejection is the norm instead of the exception is that the submission process is all backward. How often have I heard stories about famous books rejected by every traditional publisher, only to be picked up and bought en masse by a public that wanted to read that story? These anecdotes seem to enforce that submitting the traditional publishing process is broken.

Here’s how I’d fix this: instead of authors going out and saying, “Hey! I think you should publish my book,” they should instead have an internet database somewhere that allows them to upload the requisite materials usually asked for during the querying process. An author uploads the first 10 pages, a synopsis, and a cover letter. The author then adds other metadata like genre, word count, and intended audience to their submission and adds it to the database. At that point, an agent or publisher could search the database for the stories they are looking for and send acceptances to the authors who make the cut. This should cut down on the “slush pile” so many agents receive because it can filter out the authors who send queries to every available agent, hoping to hit gold with the shotgun approach.

Traditional publishing is about money.

I’ll admit one of the advantages of traditional publishing is the advance. While this sum of money is likely more than I’ve ever made on any single book, it’s also rare that an author will sell enough to pay the advance to the publisher, at which point they’d start receiving royalties. And perhaps the idea of traditional publishing is to prove you can do it once, so it’s easier to have your follow-on manuscripts be published by the same publisher—if your sales are good enough, that is; otherwise, they might drop you.

When it comes right down to it, traditional publishing is about profit. The reason authors lose the rights to their work—which then may be tweaked into something they no longer have control over—is because selling books is tough. Traditional publishers aren’t going to take risks on unprofitable genres, let alone on authors who haven’t necessarily proven themselves already marketable. Of course, the whims of the buying public are fickle and can change trends almost overnight. Some breakout success can change the game one day because a publisher took a risk that paid off, and now everyone else is scrambling to keep up. Authors are brands, and publishers like to keep these brands as focused as possible, which is why some excellent writers might never be traditionally published because they experiment with genre too much.

My decision to self-publish was mostly because of control. I like to control how my book looks and what’s inside it. I’m not the best at marketing, but I’m also writing in genres that are difficult to sell. Since I’ve decided I’m doing this for fun, I have stopped obsessing about the numbers and rather enjoying the moments where people tell me they like what I’ve written. After all, I can reach more people in this modern, connected age than I ever thought possible, and I didn’t need a traditional publisher to do so.

How about you? Have you been traditionally published?

If you’re trying to be traditionally published, why?

How long will you pursue traditional publishing?